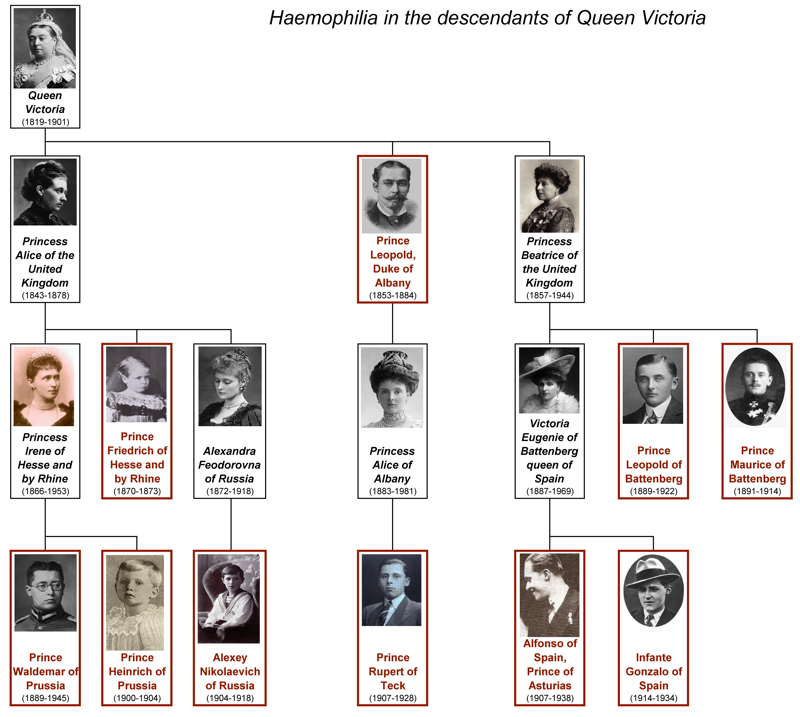

Since the Coronation, the internet and magazines have been full of pictures of Royalty. So I thought it would be appropriate to post on the “Royal Disease”, namely Haemophilia. Although this is not strictly related to taking anticoagulants, it is a serious disorder affecting clotting.

Queen Victoria

Queen Victoria was a carrier for Haemophilia. She had nine children. Her son, Prince Leopold, had severe haemophilia and two of her daughters were carriers. Several of her children married into various European Royal families and managed to take Haemophilia with them.

Haemophilia is a life-threatening condition.

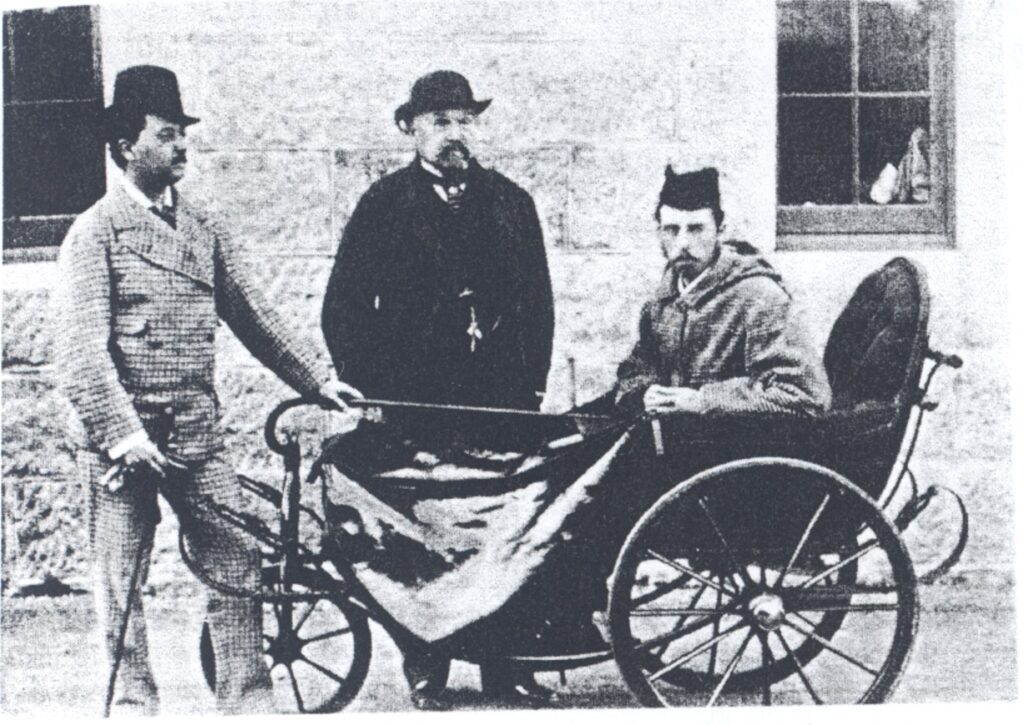

Haemophilia is a sex-linked condition, which means severe disease only affects males. Before treatment was available, boys with severe haemophilia experienced frequent spontaneous bleeds, especially into their joints and muscles. These caused severe pain and led to progressive deformity; many boys became disabled and unable to walk in childhood. Few boys with the condition lived beyond their teenage years. A common cause of death was a brain bleed following a head injury or prolonged slow bleeding. There are case reports of boys who bled to death over several days following a simple dental extraction. Fortunately, today we have treatment for this condition, and bleeds occur far less frequently.

Queen Victoria’s family

The Queen’s son, Leopold, was severely affected. His accounts of his disease make tragic reading as they describe how he was constantly in pain. The picture shows him in a bathchair, the equivalent of a wheelchair today. Surprisingly he married and had a daughter, who was also a carrier. Leopold died at the age of 31 while on holiday in the South of France. He fell on some stairs, banged his head, and died a few days later.

Queen Victoria also lost a grandson to haemophilia, Prince Frederick, known as Frittie. Frederick was only 3 when he fell from a window. He was knocked out and never regained consciousness. Shortly after the fall he developed some swelling on the scalp and gradually deteriorated and died a few hours later. Frederick’s mother, Princess Alice, never got over the shock of Frittie’s death.

Haemophilia was passed on to other European Royal families by two of Princess Alice’s daughters, Irene and Alexandra, who were both carriers. Alexandra was Alice’s sixth child and was only six years old when her mother and youngest sister died from diphtheria. After Alice’s death, Queen Victoria took a particular interest in her granddaughter, Alexandra, and they grew very close. Alexandra mixed in Royal circles and met Nicholas, the Tsar’s son, for the first time when she was 12; they immediately formed a close bond, but kept their friendship from Queen Victoria as she did not want Alexandra to marry into the Russian Royal family. Their marriage looked unlikely as Alexandra was a devout Lutheran and was unwilling to convert to the Russian Orthodox church, a requirement to marry the Tsar’s son. Eventually she relented and they married in 1894 when Alexandra was 17.

The Romanovs

To continue the Romanov line, Alexandra was expected to produce a son and heir for the Russian throne. However, between 1895 and 1901, she managed to produce four daughters. Finally, in 1904 she had a son, Alexei. Straight after his birth, all seemed well with little Alexei, but soon it was apparent he was bleeding excessively from the umbilicus. Alexandra was grief-stricken to discover her son had Haemophilia: ‘She hardly knew a day’s happiness after she realised her boy’s fate’. As well as distressing for the family, this had significant consequences for the Royal succession and future Tsar. They were a deeply religious family, and any defect was considered divine intervention. As head of the Church and leader of the people, the Tsar must be free of any physical defect, so Alexei’s haemophilia was concealed.

Rasputin

Alexei’s condition had a significant influence on Russian politics through the power of Rasputin. Alexandra suffered considerable distress and felt guilty for giving her son this condition. Doctors seemed to offer little help, but around 1907, Alexandra met Rasputin, a peasant monk who claimed to have some mystical powers. Alexandra believed that he could heal Alexei. After a severe leg bleed, Rasputin prayed over Alexei and told him, “Your pain is going away. You will soon be well. You must thank God for healing you”. Soon after Rasputin left, the swelling in Alexei’s leg went down, and the next day he was sitting up in bed fully recovered.

In 1912 Alexei had a life-threatening bleed. Again Rasputin was contacted for help, and the bleeding appeared to stop. Much is written about Rasputin, he was clearly unkempt and unpopular with many in authority, and there were rumours about his drinking and questionable morals! It is not clear how much influence he had on politics, but there is some evidence that he persuaded Alexandra to remove some ministers who believed he was a charlatan.

What causes the bleeding?

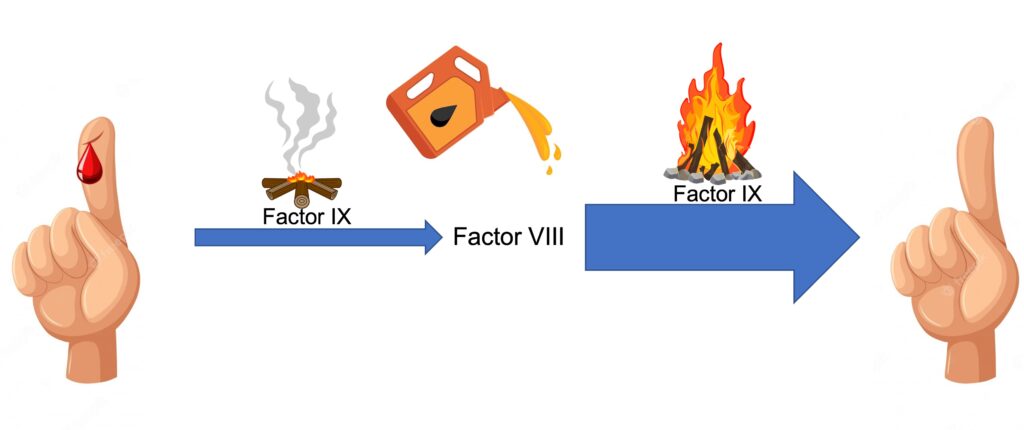

The Royal family’s story shows how one minor abnormality in the clotting pathway can cause extremely severe disease. There are two types of Haemophilia; Haemophilia A, a deficiency of the clotting factor VIII; and Haemophilia B, a deficiency of clotting factor IX. These conditions cause exactly the same problems with severe bleeding. Queen Victoria was a carrier for Haemophilia B.

In my last post, I mentioned how factor V worked and described it as an accelerant, like petrol on a fire. Factor VIII works similarly at a different part of the clotting pathway. Factor VIII is the petrol, and factor IX is the wood for the fire. Without either, the blood does not clot.

Don’t miss the next post. Click on the red “Follow” button below and be sure to get notification when the next post is available

Leave a Reply