Like the plot of a movie…

Like the plot of a movie…

Warfarin has been used as a medication for more than 60 years. The discovery of Warfarin is interesting and sounds a bit like the plot of a movie; it includes a president, dead cattle, an attempted suicide and rat poison. Like many scientific discoveries of the last century it involved some serendipity, good fortune, the correct circumstances and the determination of a few individuals.

Part 1 of the history of warfarin was about the discovery of Haemorrhagic Cattle Disease due to spoiled sweet clover,

Part 2 the actions of a desperate farmer and the churn of blood-that-would not-clot

and today, Part 3 – Karl Paul Link

Change in direction of Link’s research

Link was the son of a Lutheran pastor and the eighth of ten children. He gained his PhD in agricultural chemistry in 1925 at Wisconsin University and then spent a couple of years in Europe studying under the Nobel Laureates Fritz Pregl and Paul Karrer. He returned to Madison Wisconsin in 1927 where he was made an assistant professor.

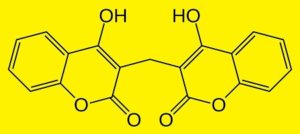

Link first heard about sweet clover disease in 1932 when he was offered a job at the Biochemistry department in Minnesota to look into the cause of the condition. He was aware that other scientists had tried to extract the relevant factor from sweet clover and had failed. Link turned down the job and went back to Wisconsin to pursue his own research in a closely related area. It was known that coumarin gave clover its sweet smell, but although it smelt sweet, the strongest smelling clover was most bitter and cattle tended to avoid eating it unless nothing else was available. Link set out to breed a strain of clover with a lower coumarin content more palatable to cows. He was working on this project when he met Ed Carlson with his dead cow and blood-that-would-not-clot.

The meeting with Carlson had a major impact on him and immediately he changed the focus of his research from clover breeding to isolating the chemical in sweet clover that caused haemorrhagic disease in cattle.

A rabbit called Bess

Link started his research when there were no reliable assays for measuring the way blood clots. He had to set up a new assay involving rabbits. He is quoted as saying the prospect of setting up a reliable bioassay were not bright; indeed they were dark, “dark like the inside of a cow”. The experiments involved feeding the rabbits spoiled hay or the relevant extracts and testing how well the rabbit’s blood clotted. A rabbit called Bess was used for over 200 experiments over 5 years.

Celebrating with ‘carpet tack’ liqueur and quoting Faust

Celebrating with ‘carpet tack’ liqueur and quoting Faust

It took Link and his team 6 years to find the chemical responsible for sweet clover disease. They extracted many chemicals from clover and frequently thought they were on the right track only to have their hopes dashed when the extract did not thin the rabbits blood.

Finally, on the morning of 28th June 1939, Campbell, a member of Link’s team, had isolated crystalline dicoumarol. He had been working all night and was sleeping on the lab couch when Link walked in in the morning. Campbell’s assistant, Boyle was taking a nip from the contents of a bottle whose bottom layer consisted of carpet tacks and the upper layer of 95% ethanol. He said to Link,” I’m celebrating Doc, Campy has hit the jackpot”.

When Campbell showed Link the chemical he’d isolated, Link quoted from Faust

“So halt’ ich’s endlich denn in meinen Händen und nenn’ es in gewissem Sinne mein”

“For when I finally hold it in my hands, I take it in a certain sense as mine”.

Using dicoumarol

Using dicoumarol

Mass production of dicoumarol took place immediately and the chemical structure was solved by April Fool’s day 1940. The synthetic chemical had the identical structure to the natural extract. Links team carried out further experiments with dicoumarol and showed that it had a slow onset of action taking a few days to have full effect, they showed that different species showed different response and that the level of vitamin K in the diet affected the response. Soon it became clear that the drug could be used safely in dogs if given at the correct dose and further studies confirmed that it reduced the risk of blood clots. This opened the way for using the drug as a therapeutic agent in humans.

Diicoumarol was introduced into clinical practice in the early 1940s and was taken up enthusiastically by some clinicians. About 50 case reports of the use of Dicoumarol had been published between 1941 and 1944. Although there was this initial flurry of activity it was interesting to see that the story of Dicoumarol followed the same cycle of events that is reported for other new medications even today.

What the journals said

What the journals said

The first reports indicated an atmosphere of great optimism and led to an editorial in Lancet in 1941 entitled, “Heparin and a rival”. Then came a period of confusion. Some enthusiasts continued to praise the merits of the drug but a growing number of sceptics condemned it as either ineffective or blatantly dangerous. Then came the third phase of consolidation where the drug became part of clinical practice but it was clear that a better alternative was required.

One area of great confusion was around the role of vitamin K as a reversal agent. Link initially showed quite clearly in some of his earliest experiments that vitamin K reverses Dicoumarol and he even stated this in his lectures to physicians at Wisconsin General Hospital and the Mayo clinic. However, when the drug was used in practice the first reports stated that, “vitamin K had no effect as an antidote”. As can happen in medicine, this incorrect statement was reiterated in several medical journals as the authors were just repeating the comments of other authors. Even some of the most senior specialists in the field made the same claim and it was even included in a leading textbook on blood disorders in 1942. It was several years before this misconception was reversed.

By the mid-1940s Dicoumarol was slowly becoming established as a useful anticoagulant. In the next part of the story I will tell you where the rat poison comes in.

Leave a Reply