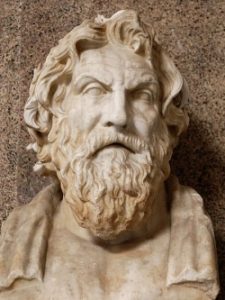

On Monday we talked about some of the mantas that are drummed into medical students as they learn the clinical skills of diagnosing medical conditions. Mnemonics are another helpful tool for medical students: These are words or phrases where each first letter represents the medical word that needs to be remembered. Traditionally, the more pornographic a mnemonic, the better, but the mnemonic used to help medical students find out about pain is instead classical, being the word Socrates.

On Monday we talked about some of the mantas that are drummed into medical students as they learn the clinical skills of diagnosing medical conditions. Mnemonics are another helpful tool for medical students: These are words or phrases where each first letter represents the medical word that needs to be remembered. Traditionally, the more pornographic a mnemonic, the better, but the mnemonic used to help medical students find out about pain is instead classical, being the word Socrates.

When taking your history, the student or doctor needs to hear your story about the pain. This gives them a good idea of what’s going on and how it impacts you. To check that there is no important information they have missed, they may use the mnemonic SOCRATES to ask questions about all possible relevant features of the pain. An experienced doctor may not need to ask all these questions to work out your diagnosis.

Site

Site

“Where exactly is the pain? Can you show me with one finger or do you need your whole hand?”

In many surgical conditions, the site of pain can be shown with one finger, but in conditions such as peritonitis, the pain is more widespread.

Onset

Onset

“When did the pain start? What were you doing then?”

If the answer is something like ‘attempting an unusual yoga pose’ then it may well be due to joints or muscles.

Character

Character

“Can you describe the pain to me?”

Some pains are constant, like a heart attack, others come and go in waves, like intestinal colic. Some pains are sharp, like Pulmonary embolism others are heavy, like a heart attack. Words like “stabbing, squeezing, aching or crushing” can be helpful

Radiation

Radiation

“Is the pain just in one place or has it moved anywhere else?”

Pain from the intestines can be felt in the shoulder tip. Pain from the heart can radiate down the arms or into the jaw. Appendicitis can start in the centre of the abdomen before moving to the lower right hand side. Pain from the gall-bladder can radiate through to the back.

Associations

Associations

“Does anything else happen while you have the pain?”

The pain of renal colic may be associated with vomiting. That of pulmonary embolism with breathlessness.

Time course

Time course

“How long have you had the pain? Have you had anything similar before”

Exacerbating/relieving factors

Exacerbating/relieving factors

“Is there anything that makes the pain better or worse.”

Often a doctor can see what helps the pain; as in appendicitis, when someone may curl up or walk in a hunched way. Two causes of severe abdominal pain lead people to respond in different ways. People with renal colic constantly move around, whereas those with peritonitis lie absolutely still.

Severity

Severity

“Did it stop you sleeping or wake you from sleep?” helps assess the severity of an adults pain.

“Show me how you can run round the bed” is a good question for children with abdominal pain to find out how severe the pain is! There are various scoring systems: adults often use a scale of 1 to 10 and children often use a smiley face chart. ![]()

Can you describe any pain you’ve had with each of these categories?

Leave a Reply